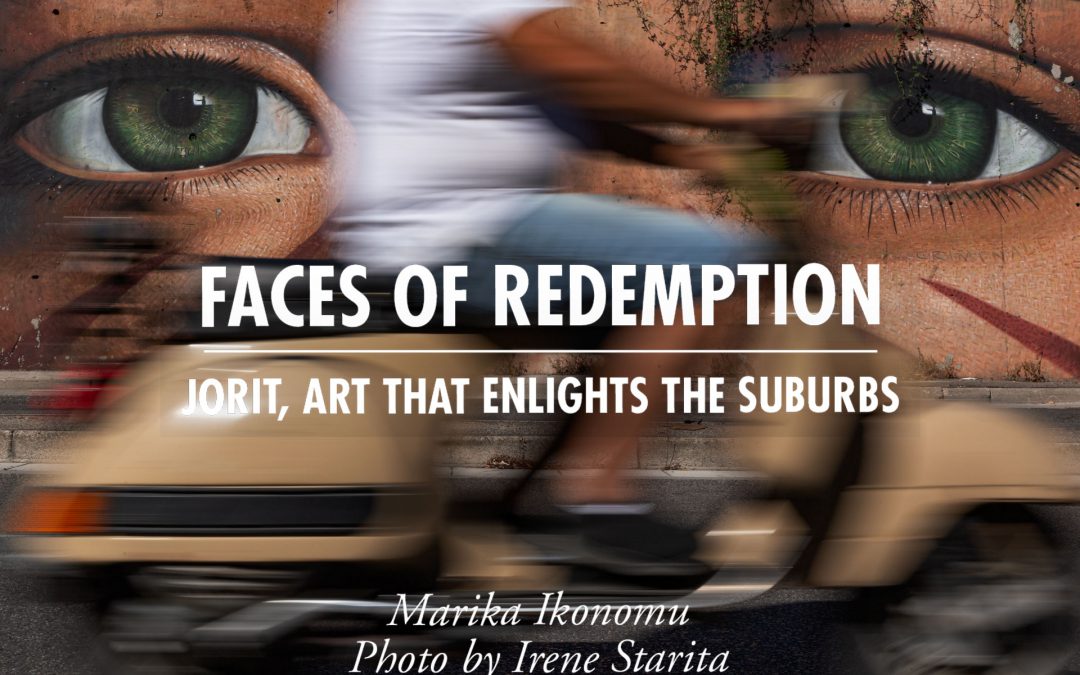

Marika Ikonomu

photo by Irene Starita

“I live here, I have always lived here and it is my life. But when I used to come home, after a few days away, and turned the corner and saw these grey buildings in front of me, I felt a pain in my chest.” Rosaria is 52 years old and has always lived in San Giovanni a Teduccio, a neighbourhood in the eastern suburbs of Naples. “Before these works, these buildings were a disgrace, you couldn’t look at them,” says Rosaria, looking at the two murals that now occupy the façades of the west side of the “Bronx”.

Since 2018, the four building façades have had the colour of redemption: Diego Armando Maradona, Niccolò, Ernesto Che Guevara, the man and the soldier, keep watch over the residents of the former Taverna del Ferro housing estate. Huge faces created by Jorit Agoch, the world-famous Neapolitan artist who paints with spray cans. The distinctive feature of his murals is the red scars on the cheeks. “I am in love with these works. Tourists come to see them. Sometimes I stand in front of Maradona and I say: «Come round to the other side, Che Guevara is here»!” says Rosaria laughing. She speaks passionately about the place where she lives, but does not hide the daily struggle to make the council houses in San Giovanni, forgotten by the institutions, in which 360 families live, decent. However, the two Che Guevaras have changed the appearance and the impact of this place and Rosaria is so proud that she even has one of them tattooed on her right arm: Ernesto the man.

Niccolò and Diego Armando Maradona (dios es umano), San Giovanni a Teduccio (Napoli)

The council houses of the former Taverna del Ferro estate are known as ‘the Bronx’, but the inhabitants and the ‘Battle Committee’, of which Rosaria is one of the most active members, are trying to get rid of this name and make it a more liveable place for the more than one thousand people who call it home. “Thanks partly to these murals, we were able to bring the issues of Taverna del Ferro to national attention,” explains another activist of the committee, Salvatore. San Giovanni, as told by those who live there, continues to deteriorate in terms of liveability, especially in terms of environmental issues. “It has been forgotten, it doesn’t even seem like Naples!” they complain.

The two buildings, built after the 1980 earthquake, were supposed to be temporary social housing, but many people have been living there for forty years. The idea was to reproduce the very narrow streets of Campania’s main city. The street dividing the two eight-storey buildings is, in fact, narrow and dark. Salvatore explains that “until about ten years ago, there were communicating bridges between the two buildings and all the houses were connected. It had become a drug den, and those connections allowed people to escape”. “The houses are in a state of disrepair, it is raining in people’s homes,” complains the committee. But the paintings changed the face of the buildings and encouraged funding from institutions. Some renovation work is already underway and funds have been allocated for re-roofing and for a demolition and reconstruction project, which is included in the works of the National Recovery Plan.

The girls and boys of the neighbourhood, says Rosaria, “fell in love with Jorit”, who lived that reality to the full during the forty days he spent painting the two Che Guevaras, explaining to them the story behind the work. “Bringing profound themes into the close-knit community of a neighbourhood or district” is the aim of Jorit’s committed art, according to the artist himself.

Che Guevara man and soldier, San Giovanni a Teduccio (Napoli)

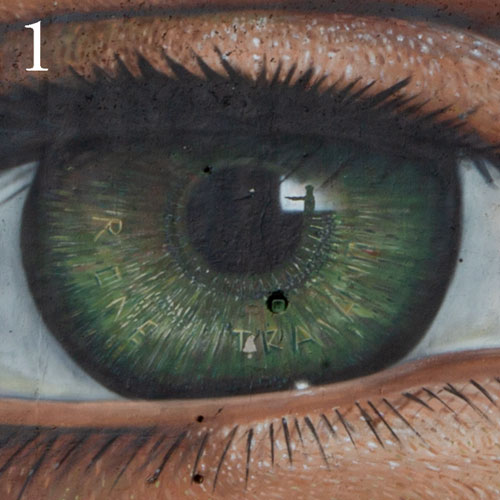

In most cases, Jorit explains, he chooses who to represent, “based on the value and message that certain historical or contemporary figures can convey”. “The face is the figurative part that communicates directly and quickly,” he says. “You cannot turn away from a face. I think it’s a very powerful means of communication, especially when those faces spread messages and ideals”. In San Giovanni, in fact, the inhabitants only found out who would be depicted once the work had begun, with the exception of one mural, the one depicting Niccolò, a boy with autism. “The boy’s father had it done. It is a message against bullying,” explains Enrico, a middle-aged man living in the neighbourhood.

Despite the committee’s appeals, the local council has not contributed in any way to Jorit’s works. A bottom-up fund-raising campaign was launched: “We set up a stall and everyone participated, even the inhabitants of these buildings. They gave one or two Euro, whatever they could afford,” says Rosaria. The committee then found sponsors who provided a platform, which is very expensive and essential for Jorit’s works, given their size.

The 31-year-old Jorit Agoch was born and raised in Quarto, a town near Naples. Of Neapolitan father and Dutch mother, he started drawing graffiti at the age of thirteen, in Quarto Officina, tagging walls and trains. “Then I focused more on faces and started to make them bigger and bigger,” says Jorit, who has “always had a passion for drawing, ever since I was a child”.

He then attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Naples and studied at the Tinga Tinga International Art School in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, where he honed his technique. The first large face painted in Campania’s capital is that of Ael, which in the Romani language means “she who looks at the sky”. A Romany girl, with a strong gaze, armed with books and a pencil, and initially with a ‘strummolo’, or spinning top, which has since been erased, just as some of the books have been erased. “Ael. Tutt’ egual song’ e creature‘, is the title of the work in Ponticelli, produced as part of the national campaign “Switch on your mind, switch off prejudice”. Ponticelli was, in fact, the scene of an arson attack in 2008 that destroyed the Romany camp where around 1,500 people lived.

Ael. Tutt’ egual song’ e creature, Ponticelli (Napoli)

Testimonials

Perchè i volti

Gli inizi

Cultura in rioni e quartieri

I segni sul volto

Street art nelle periferie

Video interviste di Marika Ikonomu, musiche di Lamberto Macchi

di Irene Starita, Musiche di Sinnermann

From Ponticelli, he went to Forcella, a working-class neighbourhood in the centre of Naples, where he painted San Gennaro, the city’s patron saint, with the human face of an ordinary man. Most of the works are in Naples: Angela Davis and Pier Paolo Pasolini are in Scampia, Ilaria Cucchi in Arenella, Davide Bifolco in the Traiano district, Salvador Allende and Martin Luther King in Barra, and many more. He has brought faces symbolising battles for civil and social rights not only to Italy – in Rome, Florence, Diamante (in the province of Cosenza) – but also to other countries, such as Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Tanzania and China. The person depicted does not necessarily have blood ties to the place: “I like to decontextualise,” explains the artist, who, for example, painted Martin Luther King’s face in Barra, a suburb of Naples, because “certain ideals and values are universal”. And he emphasises: “Bringing high values, bringing Pasolini to Scampia, reinforces the message I want to convey even more”.

Davide Bifolco, Traiano (Napoli)

He sends these messages not only through the faces, but also through the writing on the background of the murals and the elements or words hidden on the face, often within the iris. The idea behind his works, the artist explains, “is that we should all start from the same starting blocks. Everyone should have the same rights and opportunities. A world that puts the community first”.

And uniting ideals, values and faces is the artist’s distinctive feature: all the people depicted have red scars on their cheeks, a symbol “of belonging to the human tribe, a concept of brotherhood and roots”, says Jorit, whose tribe is called the HumanTribe. These marks relate to African initiation rites, representing the passage from childhood to adulthood and the individual’s entry into the tribe. So the artist from Quarto also has his distinctive feature on his right cheek, marking his transition to adulthood.

Ilaria Cucchi, Arenella (Napoli)

Patrizio Oliva, Nando De Napoli, Carmelo Imbriani, Antonietta De Martino, Nando Gentile, Quartiere Direzionale (Napoli)

Each mural has its own story. It becomes part of the urban landscape, changes it and influences it. It asks questions of those who look at it, the ones who live there and those who are just passing through. And it helps to keep a memory alive, as is the case in Tufello, a working-class neighbourhood in Rome with a particular political history and a drama that has become a symbol. On the wall of a school in the district’s main street, Jorit painted Valerio Verbano, a young man killed on 22 February 1980, at the age of just 19. The assassination was claimed by the Revolutionary Armed Nuclei, an Italian neo-fascist terrorist organisation. Valerio Verbano was politically active and he was investigating and gathering information on right-wing extremism in Rome. After 40 years, no one has been found guilty of the murder and the neighbourhood remembers him every 22 February. “The mural is part of the work we are doing in memory of Valerio and his parents, Carla and Sardo,” explains Giulio from the ‘Palestra popolare del Tufello’, a social organisation named after Valerio Verbano that does important work in the neighbourhood. “Every year, we try to refresh that memory and, to do so, we try to talk about topical issues. We ask ourselves: what does that memory represent today? How is it transformed and what does it mean now?” continues Giulio, who points out: “We have always been convinced that talking about the memory in order to carry the flag of history is important, but not sufficient. We have to bring it into the present”.

Valerio Verbano, Tufello (Roma)

The work for Valerio Verbano was done for the fortieth anniversary of his death and is part of the set of works dedicated to this story, shared and deeply felt not only in the neighbourhood, but in the whole city. “We had to do something a little bigger and more important and leave a mark,” says Giulio. The administration of Rome’s third municipal subdivision contributed to the project, because it “cares about keeping the memory of Valerio Verbano alive”, but the request came from below.

It was this grass roots demand that lead the public body to fund the work. “The request always comes from the committees, the associations, the people in the neighbourhood,” explains Jorit. In San Giovanni a Teduccio, on the other hand, the institutions have abandoned the works, complain the citizens. “Even the New York Times talked about the murals in San Giovanni,” says Salvatore, of the former Taverna del Ferro committee. “Small actions by the local council would be enough. Four floodlights to illuminate them at night, look after the flowerbeds underneath, control the dumping of rubbish. Few resources are needed, but a lot of attention. You can have the artwork, but if you don’t build up interest, you don’t go anywhere,” he continues.

These works remain the heritage of the area and have helped to bring many issues to light. “Eastern Naples is now on the political agenda of the local council and the regional government,” the committee says.

In the absence of public grants, Enrico started a collection to fix the mural of Diego Armando Maradona, the largest in the world depicting the Argentinian footballer. It is Enrico who takes care of the little square, named after the footballer, because “Maradona is like us” he says, referring to the redemption of a man and a neighbourhood.