the history of aerosol

circa 15,500 b.c.

THE LASCAUX CAVES

the first artistic aerosol

The Montignacsur-Vézére Valley in the Dordogne, in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of Southwest France, kept a priceless collection of artistic treasures hidden for many millennia: the Lascaux caves. The walls of this extremely ancient natural site were frequented and decorated by prehistoric humans and are home to an incredible series of cave paintings that serve as testimony of the artistic sensitivity and expressive skills and techniques of the populations that lived in that part of Europe between 18,000 and 17,000 years ago. The various techniques include the first use of an aerosol technique in art, in which the colours were mixed with saliva inside the painter’s mouth and then sprayed onto the rock. This technique was probably used to create the famous “silhouettes of hands” discovered at various wall painting sites in France and Spain. There is also the colour blowing technique, in which a small pipe fashioned from animal bone was filled with paint: a surprising, albeit rudimentary and primitive, forerunner of the airbrush that would be designed twenty millennia later, in the second half of the nineteenth century, when humankind already had electricity, the telegraph and the combustion engine. This offers further proof that intuition may be ancient, but only modern and contemporary technologies have allowed the best, most ingenious and rational developments.

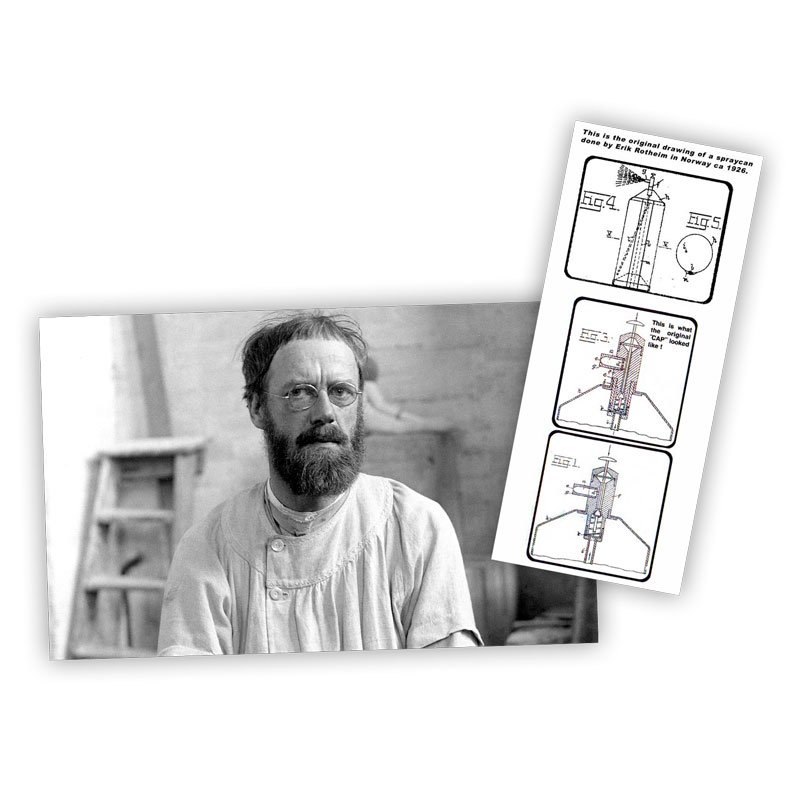

1926

erik rotheim

the thomas edison of the spray can

When the last of these experiments were being performed and the “first steps” were being taken, the man who would go on to become the “Thomas Edison of the spray can” was just a child, living a carefree childhood in Kristiania, as Oslo was called at the time, the Scandinavian city that had just surpassed Bergen as the most populous city of Norway. His name was Erik Rotheim. After the First World War, he went to Switzerland to complete his studies and became a young and talented chemical engineer, specialising in electrochemistry, but also with many other interests. In October 1926, when Rotheim (1898-1938) was just twenty-eight years old, but already well-established thanks to extensive and important laboratory experience, he filed a revolutionary patent application in his native land for the first, real spray can: a metal container that dispensed fluids through use of a chemical propellent (vinyl chloride monomer (VCM), or dimethyl ether (DME), a by-product of methanol processing) and a valve that implemented and improved the idea of the Austrian, Gebauer. The ingenuity of Rotheim was stimulated by the need to create a method to spray compounds for coatings that used paints, soaps and resins as the substances to be nebulised.

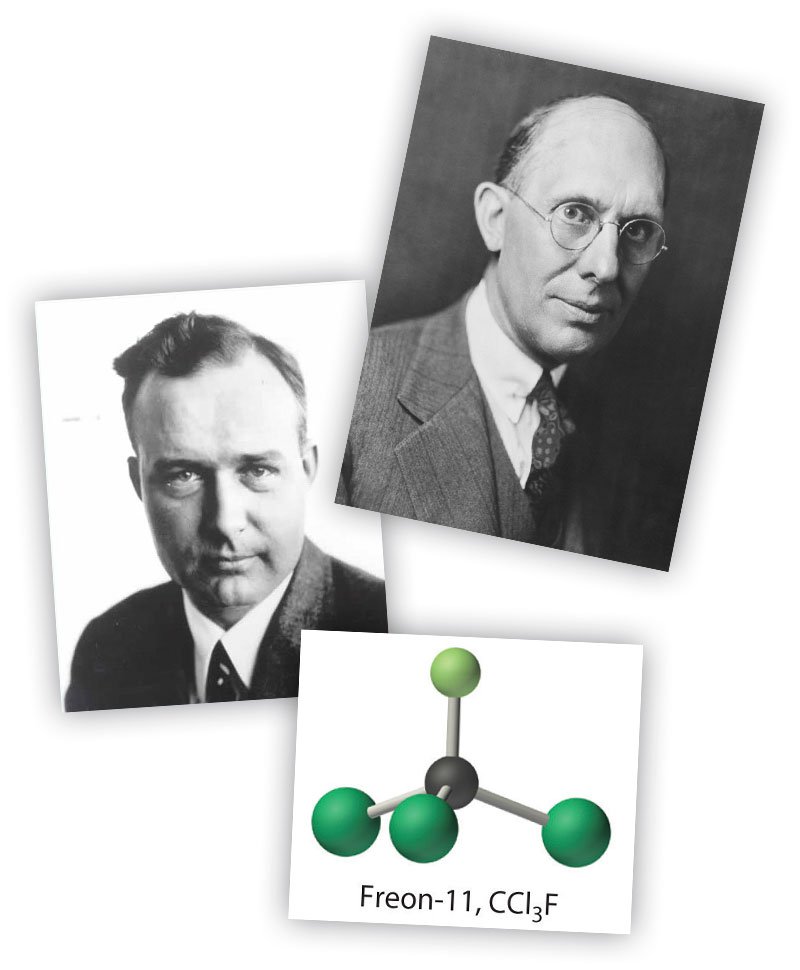

1930

Thomas Midgley and Charles Kettering

THE CREATION OF FREON

During the same period in which the Norwegian Rotheim was working to create his devices to obtain efficient and usable aerosols, the American chemical engineer Thomas Midgley (1889-1944), assisted by his older fellow researcher and industrial manager, Charles Franklin Kettering (1876-1958), was creating a new refrigerant gas:

dichlorodifluoromethane, a fluorocarbon with low toxicity and the prototype of chlorofluorocarbons. The product was manufactured by DuPont with the commercial name of Freon. As a result of its many positive characteristics, it was soon “recruited” as the main refrigerant fluid in compression refrigeration cycles. This efficient and versatile synthetic product, colourless and with a slightly ethereal scent, was destined to become – together with other easy to liquefy gases, such as propane, butane and isobutane – one of the main propellants for aerosol cans. This continued until 1989, when its use was prohibited by the major international organisations, as it was judged to be harmful for the ozone layer. From that point on, it would be replaced by the “fourth generation gases” that do not damage the ozone layer, particularly purified LPG for aerosol use, tetrafluoroethane HFC 134a and, in more recent years, tetrafluoropropene HFO 1234ze.

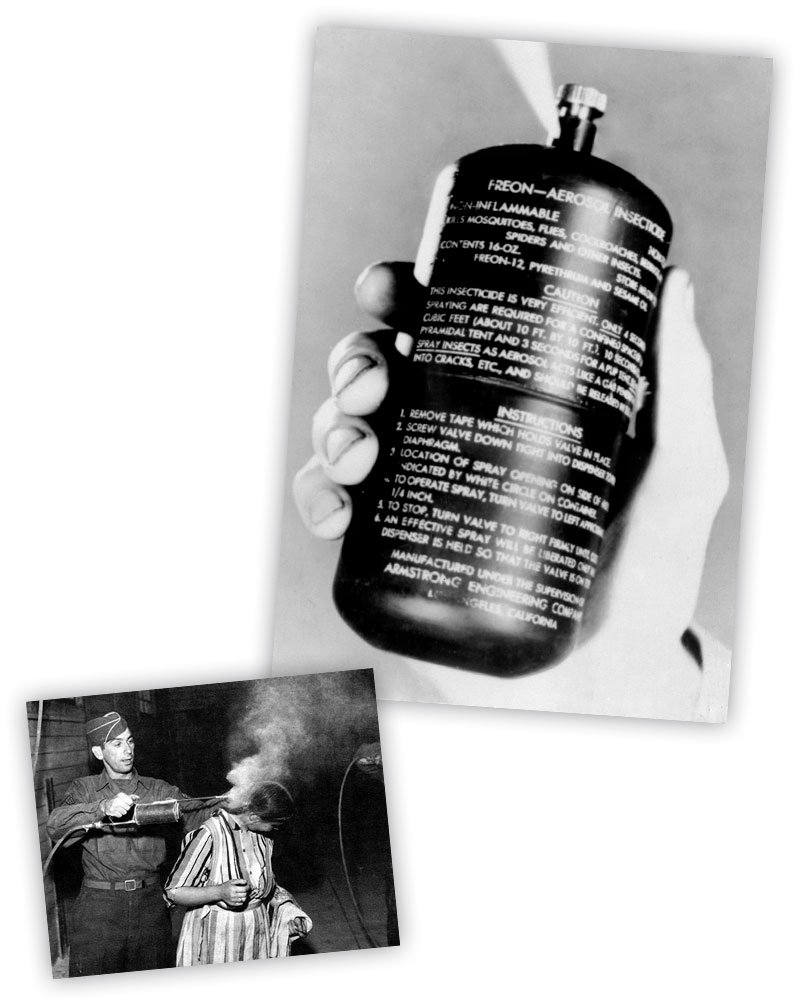

1942

ddt

THE FIRST SPRAY INSECTICIDE

The many needs of the war included strong demand for a portable insecticide. The greatest increase in demand came from the US airborne troops fighting in areas – such as the Pacific islands and peninsula – infested with insects that were carriers of serious diseases, such as the Anopheles mosquito, carrier of malaria. This demand from the highest military echelons was covered by Westinghouse, which, in the summer of 1942, signed a contract to supply the US armed forces with industrial quantities of “aerosol” spray cans containing a propellant gas and non-toxic liquid insecticide. The company supplied the US Army and Air force with over 30 million cans between 1942 and 1945. However, the true scientific “father” of this application, which, after influencing the outcome of the war in Asia, would, without exaggeration, change the habits of most inhabitants of the planet, was a brilliant chemist and inventor in Iowa, still under forty years of age at the time: Lyle Goodhue (1903-1981). The first experiments conducted by Goodhue using valves and aerosol propellants dated to around a decade previously, in 1929-30, when, as a young researcher into lacquer formulations at the DuPont Chemical laboratories in Parlin, New Jersey, he had started working on the technology recently conceived by Erik Rotheim and just imported into the United States. His work on the topic continued until 1935 and a new cycle of tests he performed at the Agricultural Research Center of the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) in Beltsville, Maryland. Here, in early 1941, the busy chemist began feverishly researching and assembling components and ingredients. In the spring of that same year, Goodhue had already successfully tested his first version of the insecticide spray can and went on to file the patent shortly afterwards. Success came on Easter Day (13 April 1941), on completion of a test in which the chemist tested the aerosol spray he had obtained on several dozen cockroaches. Years later, Goodhue would remember that historic moment with these words: “In less than 10 minutes, all were on their backs. No one else was in the building. I yelled at the top of my voice and danced around wildly. As soon as I could regain my composure, I drove home like a mad man and called Bill Sullivan and John Fales, and with great enthusiasm gave them the results of the first test”. Those several dozen cockroaches who had been turned on their backs in just a few minutes by the spray from Goodhue’s nozzle marked the beginning of the era of sprays. Assisted by a talented, young entomologist who was serving in the US Air Force at the time, William N. Sullivan (1908-1979), Goodhue filed a second patent in 1943, for the more complete and improved insecticide aerosol “dispenser”. The project was assigned to the US government and was effectively the “forefather” of many famous spray products that are still sold today.

1948

Carl Svendsen

THE FIRST HAIR LACQUER SPRAY

In 1948, Chase Products Company, an insecticide and pesticide manufacturer in Illinois, founded around twenty years previously and run at the time by the young Carl Svendsen (1923-2000), was the first company to invent and market a hair lacquer, mixing a copolymer of polyvinylpyrrolidone with a propellant formed of carbon, fluorine and alkyl halides.

1949

A SOFT AEROSOL

ON MEN’S FACES

THE FIRST SHAVING FOAM SPRAY

In 1948, Chase Products Company, an insecticide and pesticide manufacturer in Illinois, founded around twenty years previously and run at the time by the young Carl Svendsen (1923-2000), was the first company to invent and market a hair lacquer, mixing a copolymer of polyvinylpyrrolidone with a propellant formed of carbon, fluorine and alkyl halides.

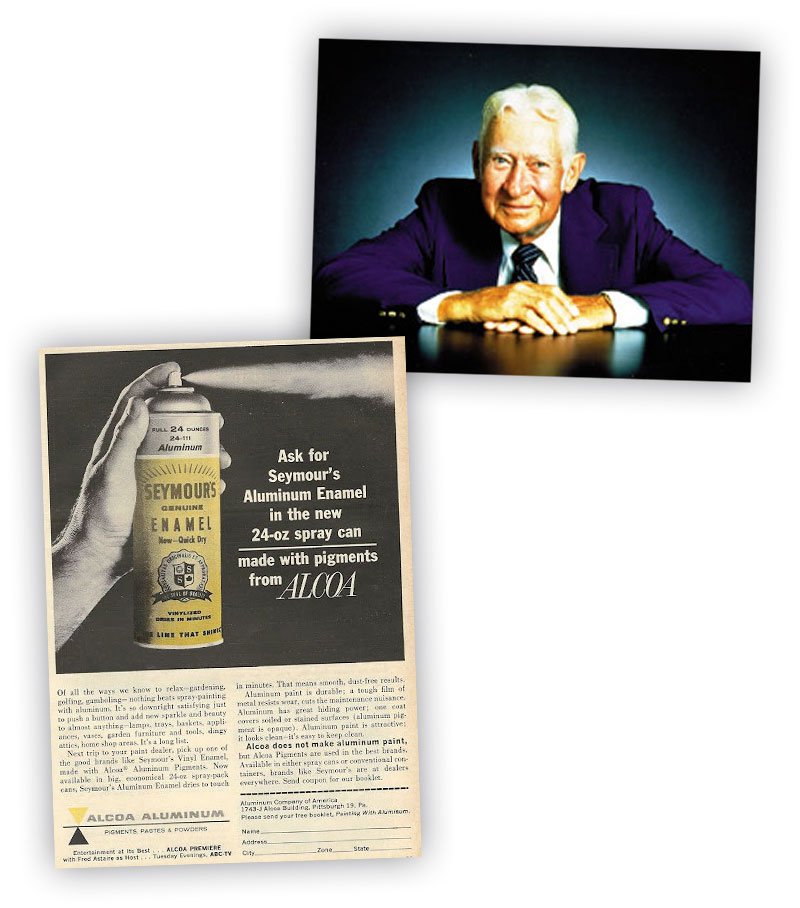

1949

colourful clouds

paint spray cans

Ed Seymour, the owner of a paint company in Sycamore, Illinois, was seeking a simple method to demonstrate the effectiveness of its aluminium paints for radiators. His wife had suggested an improvised spray pistol, like the ones used for deodorants. In 1949, Seymour mixed together paint and aerosol in a can with a spray nozzle. He thus discovered how efficient and even the colour was when applied in this manner and manufactured the first paint spray can.

1953

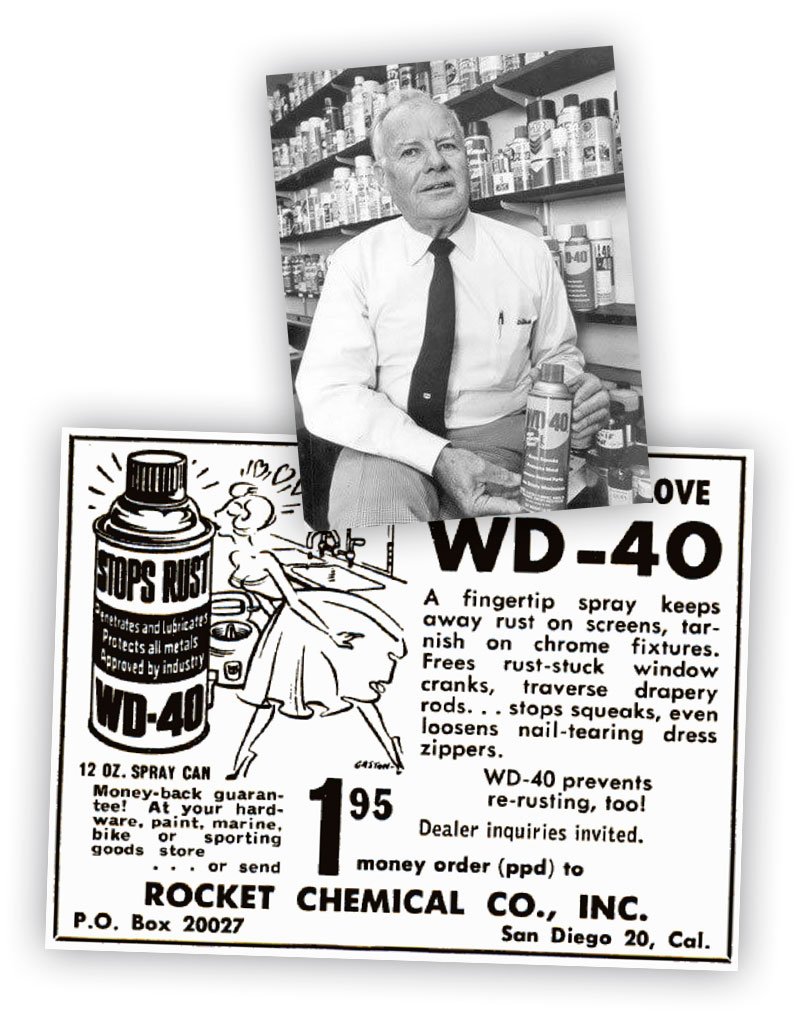

wd-40

THE “MAGIC” SPRAY THAT LUBRICATES,

LOOSENS AND CLEANS

Norman Larson invents the multifunctional spray (water repellent, lubricant, anti-corrosion, unblocking, detergent) WD-40, a product of surprising effectiveness and versatility

After a few years of high-level military use on the first ICBMs, it begins to be marketed in some Californian stores.

1960

fragrant clouds

FROM SCENTED OILS AND OINTMENTS TO SPRAYS

All the classic civilizations of the Mediterranean (Egyptians, Greeks, Phoenicians, Hebrews, Etruscans, Romans) and the tribes of the Arabian peninsula made extensive use of mixtures of scented oils ad plant aromas (such as myrrh, incense and aloe, which have been used for centuries) to deodorise themselves and their surroundings and to celebrate and to sanctify. What really boosted the perfumes market, however, was unquestionably the discovery of the art of distillation by Arabian scientists between late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Avicenna (Ibn Sina), a celebrated Persian doctor, mathematician and physicist of the tenth century, then discovered how to distil the famous “rose water” from the petals of the cabbage rose. However, since alcohol was forbidden by the Koran, the sacred book of Islam, the excipients used to create the scented waters remained oily. It would only be the Higher Institute of Sciences of Salerno, in around the year 1000, that would replace the oil with alcohol as the excipient of the perfumes. Around the mid Twentieth Century, the invention of the spray can (started between the two wars, but perfected, completed and widely available only after the Second World War) become the principal and most efficient “ally” of perfumes. The practical and portable dispensers, easy dosage and refreshing effect of the spray on the skin were the factors behind the massive success of spray perfumes and deodorants for personal and home care, extending their use and the market to the entire world. Spray deodorants for men and women became popular between 1950 and 1960, as a valid alternative to creams, pastes, sticks and roll-ons. They contained propellants (chlorofluorocarbons) and antiperspirants such as zinc chloride and aluminium salts, creating a market that is still vast and flourishing today, although with numerous variations in terms of the substances they contain and the production technologies.

THE 1960s

SPRAYING WALLS AROUND THE WORLD

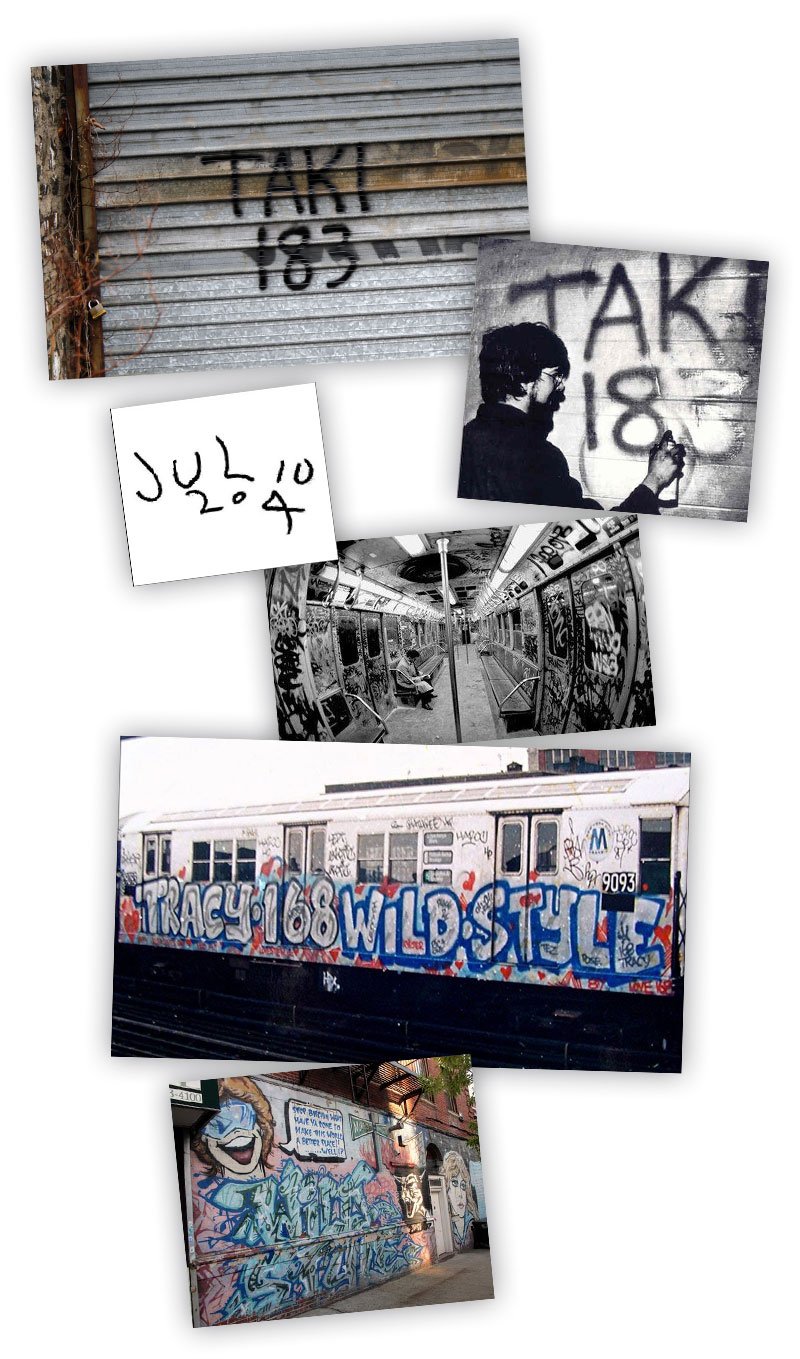

“GRAFFITI WRITING” AND AEROSOL

The first true writers of whom we have some testimony and knowledge (as already said) were probably the unknown artists, both male and female, of the Upper Palaeolithic Age who started using colours obtained from ochre, earth and carbons to decorate the walls of caves in the Franco-Cantabrian region between modern-day Western France and Spain. It is truly singular to note how the same desire for expression and communication links these anonymous artists from 20,000 years ago to the artists and movements of more recent times, still living and writing on the walls: the so-called graffiti writers, part of a movement that started over half a century ago on the Eastern Coast of the United States, between Philadelphia and New York, but then spread to urban areas across the planet. Graffiti is a specific discipline with its own, self-imposed rules, not to be confused with the wider and more eclectic world of street art, in which a wide range of techniques are used. The catalyst behind this particular art form – which almost certainly started in the early 1960s, and not in the early 1970s as frequently thought – was mass marketing of paint spray cans, which offered young people on the outskirts of urban areas the ideal portable and efficient means of writing on walls and on other surfaces visible to the public, big or small. It is unclear when and where the first spray graffiti appeared, but the first modern-day writer is assumed to be a Greek-American who lived in New York and used the “tag” TAKI 183. He was later identified as Demetrius …… (1953), a young resident of the “Big Apple” of Balkan origins, who remained active as a graffiti writer for an extremely short period, between the end of the 1960s and the early 1970s. In several interviews, “Taki” also mentioned another graffiti writer, a Puerto Rican who lived in the Inwood neighbourhood of Manhattan and started using his tag – JULIO 204 – in around 1967-68, or maybe even before, which would make him the original New York City writer. It is clear that no more than fifteen years passed between marketing of the first spray paint cans (conceived by Edward Seymour) and the first wall writing. Individual tags, political and social statements and the turf markings of the street gangs were the type of spray can writing that started proliferating on the walls of New York and Philadelphia in around 1970-71, and then in other US cities. At a certain point, it crossed the Atlantic and the Pacific to become a worldwide language. The roots of the development of this new form of communication therefore lie at least partly in the contexts of urban decay and marginalisation. It was only later, between 1970 and 1980, that graffiti writing would gradually be refined and stylised, creating its own stylistic principles and precise rules and becoming a much more complex cultural phenomenon. It would then “take flight” as a genuine new art form.

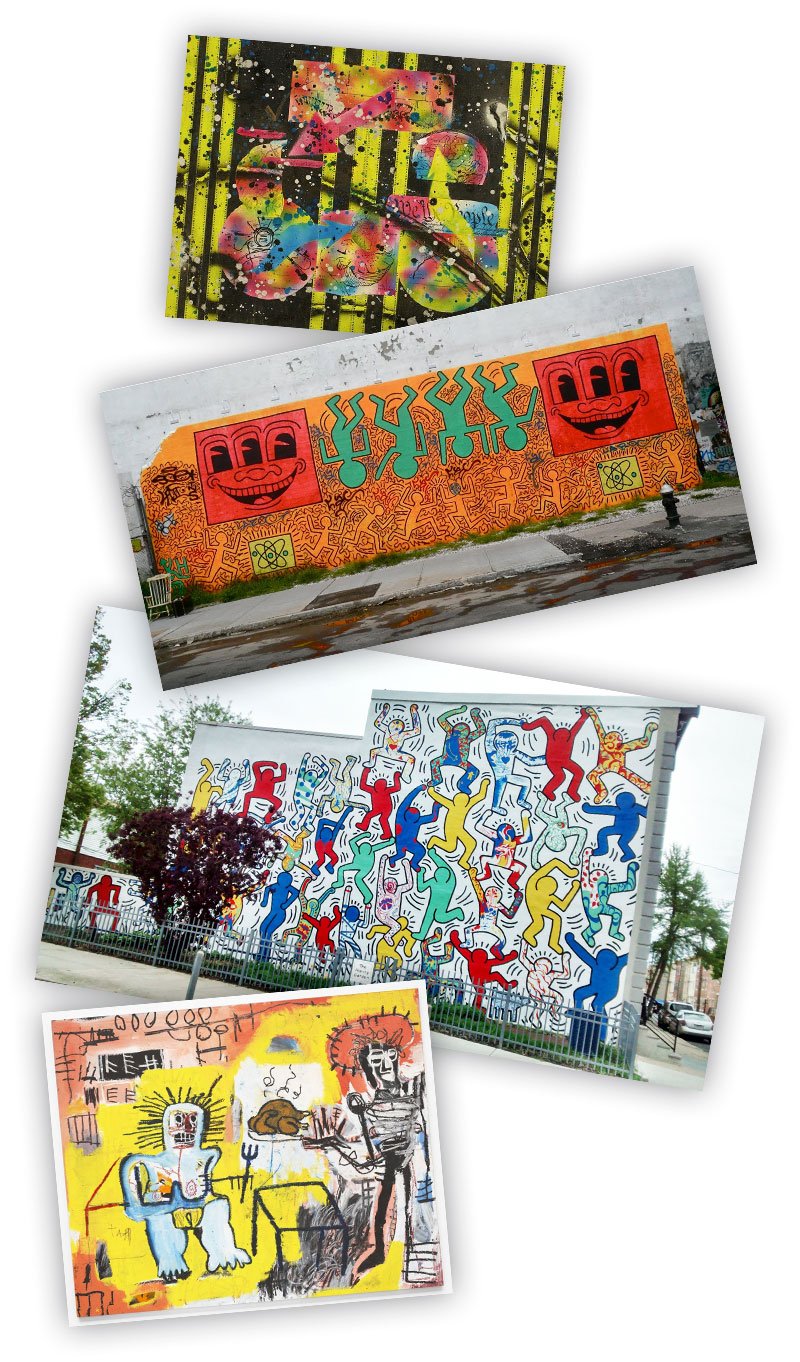

THE 1970s AND 1980s

FROM URBAN DECAY TO ART GALLERIES

The appearance of the Taki tag and the more mysterious Julio on the walls of New York came almost fifteen years before the wave of serial graffiti art associated with the hip-hop culture and the more “cultured” and mature graffiti of the 1980s. The great pioneers of this second phase of writing undoubtedly include the highly original name Rammellzzee (1960-2010), an eclectic multimedia artist of Afro-American and Italian origins, who grew up in the Queens borough of New York and started his graffiti writing career on the A-train of the New York Subway in the mid-1970s. He went on to contextualise his work and even came up with his own theory of visual art, called Gothic Futurism. This new group of urban writers, who focused more heavily on art and its wider use, rather than a simply self-referential style of communication, was spearheaded by the gifted young artist Keith Haring: using a spray can, but also tracing unmistakable outlines with white and coloured chalk and magic marker pens, this highly active artist, who came to New York from Pennsylvania, drew everyone’s attention, gaining praise from major critics and gallery owners. In 1982, his first personal exhibition, organised by the powerful gallery owner, Tony Shafrazi, consecrated him as a world-renowned artist. The Armenian and Anglo-American Shafrazi (1943) had himself been, just eight years before, the visual artist who spray-painted Picasso’s celebrated painting Guernica, as an act of political and intellectual provocation. Everybody recognises the simple and penetrating magic of Haring’s figures – particularly the famous radiant boys, the stylised figures that move and are interwoven dynamically into the works – and his “flat” and aperspectival backgrounds, almost an “official” graphic representation of the early 1980s. Haring also become a celebrity in Europe, where he went when he was already a well-established artist in New York and where he created new works, several of which have, unfortunately, been lost. A similar path was taken by his almost-contemporary Jean-Michel Basquiat, an American of Haitian and Puerto Rican descent, from the temporariness and residuality of his graffiti “duo” (1977-1980) with the young Hispanic-American writer Al Diaz, using the tag SAMO (SAMe Old Shit,), to definition of his own style, as recognisable as Haring’s, and the glorious lights of the art galleries. Another decisive factor for him, in addition to his friendship with the guru of pop art Andy Warhol, was the enthusiasm of the critics and gallery owners. In 1982, the Italian gallery owner, curator and lecturer who had moved to America, Annina Nosei, organised his first “personal exhibition” at her gallery in the Soho district of New York. Basquiat’s paintings – decidedly collage-style, schematic, deliberately unrefined and infantile, as well as being frequently “contaminated” with words and quotations – would soon become as iconic as those of his friend Haring. It could therefore be said that 1982 was the watershed between the pioneering period of street art and the period in which the movement and its leading exponents were transformed into and consecrated as successful artists.

1997

banksy

The contemporary evolution of street art looks towards broader and more diversified horizons. After spending years contaminating areas such as graphics, computer graphics, illustration, fashion and design, the street art of the first quarter of the third millennium would seem to be pursuing complex artistic objectives. The icon of the world movement, in the first decade of the twenty-first century, was unquestionably the anonymous (even now) British artist who goes by the name of Banksy (born, it would seem, in 1974), an extremely active street artist whose works are heavily social and political, often with a sarcastic and paradoxical tone. His original creations occasionally appear suddenly in museums and art galleries. From the first, historical mural on a wall in Bristol in 1997, the mysterious Banksy, with his unexpected exhibitions in western cities, has gradually become the world’s most famous street artist.